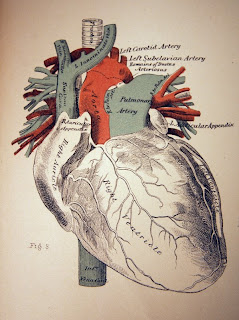

But the years have kept coming, somehow, with the kidney biopsy tucked in the day after my comprehensive exams. My hospital roommate a woman who cried that she was afraid of the ghosts; my view the strange, small India Point bay in Rhode Island. My doctor a small, kind man, congratulating me on passing exams. The old cliches, "Do you want to good news or the bad news first?"

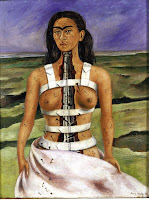

Now back in New Mexico it was three years of a dream. Snow for months, wet socks and umbrellas, crab cheaper than beef, brick walls that really supported ivy, drives cross country--Graceland and tornadoes and the Blue Ridge and Travel America and DC and ice rain. Somehow the books and the dogs and the cats and I got back here. Somehow through rashes and fatigue and the frustration of almost never being able to call forth the exact word I want to say, somehow I got back. I am still stunned with every sunrise, I am still terrified with every small ache, I still avoid the thermometer for fear of confirmation that I am really, and truly ill and must report to ER.

I am back planting. I am back reading. I am back building fires and making stew and hanging out casual-like, I am back petting the cat. The everyday is still stunning to me almost 12 years since the biggest of all big medical events. This time of year owns me in a way no other time does--the season when my life always changes, the season when Mother's Day opens to Father's Day and I celebrate my survival with both joy and confusion. Never feeling worthy of the effort the doctors and nurses and family have invested in my survival. "But look!" I want to say, "Sometimes I can do a really nice thing." But that's only sometimes.

We all survive in these bodies. We all come back around over and over, to May, to June, to the sound of rushing water that once caused infection but will now irrigate fields, to the sound of rushing water that is now a blessing. It is again, my Spring.